How bots vote: insights from 100 Instagram polls

During the 2020 period of social distancing, I conducted 100 Instagram polls with questions ranging from the mundane to the hard-hitting. This essay outlines my key findings, including novel observations on the perfect predictability of voting patterns among bot accounts.

Social distancing measures were put into place — either officially or unofficially — in the United States sometime during March 2020. I began working from home and stopped going out, and so did a lot of people I know. As everyone spent more time staying in, I noticed that more people were going on social media. During the first few weeks of social distancing, the content I saw on Instagram collectively took an interesting turn. Suddenly, the people I knew from different scenes, different states, and different political leanings were all posting surprisingly similar things on their Instagram Stories. Examples of popular posts include:

Doing 10 push-ups, and then tagging a few friends to also do 10 push-ups

Filled-in bingo cards that were specific to a particular experience, such as attending a specific college, being part of a specific interest group, or living in a specific city

A “30-day song challenge” in which people posted songs they liked every day for 30 consecutive days

I did not do any of those popular posts. Despite being athletic enough to have finished first in a spin class, the truth is that I cannot do a single push-up, let alone 10. I still wince when I think about the random physical fitness assessments we had in high school P.E. class and I always had to report having done zero push-ups in a minute. (I don’t know why this has been so difficult for me. Maybe I have very weak arms? I’m not even positive that I can properly do a push-up on my knees today. It never feels like I’m doing it right.)

During this time, I inadvertently wound up creating what was — by my commoner, peasant standards — my most successful series yet on social media. Feeling emboldened by the belief that I had nothing to lose and suspecting that anything original I did was bound to be more entertaining than a video of me failing to do push-ups, I began to post polls onto my Instagram Stories.

Prior to the era of social distancing, I had used the poll function on Instagram before, but only sporadically and for superficial questions. For instance, when I was in Hong Kong one summer and saw a banner advertising cheese tea, I took a picture of the banner for my Stories and added a poll that said: “Cheese tea: yay or nay?”. In the absence of interesting surroundings while sitting at home alone, my poll questions got deep fast, and many of them were about things that are not visible. Seven questions in, I asked, “Would you date someone exactly like yourself?” — no context, simple white text on a black background, a format that would remain consistent throughout the project. Ordinarily, I would have considered a question like that pretty “out there” for social media, but this time I was like, fuck it. All of the questions were derived from thoughts that recently came to mind, and I posted my polls on the fly.

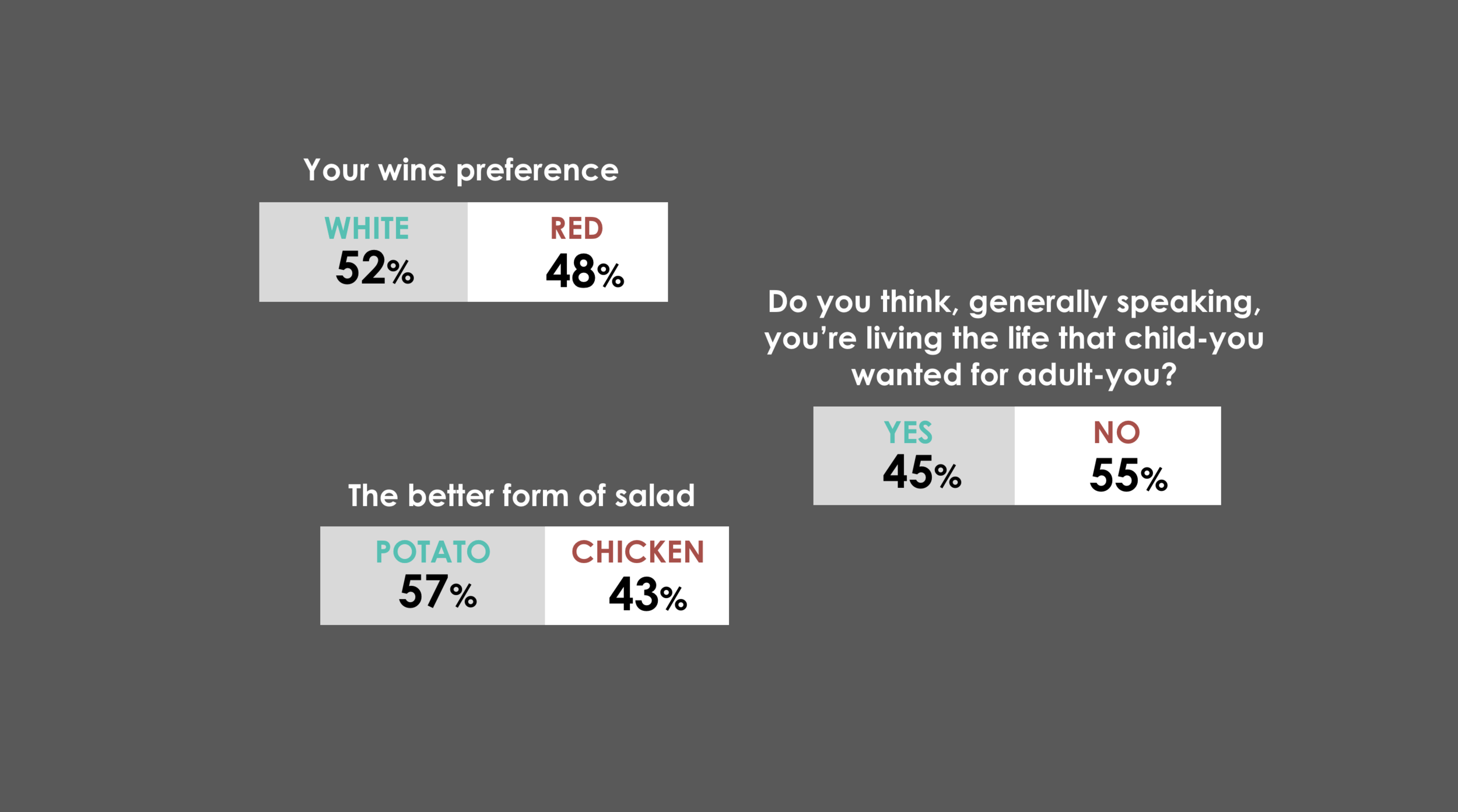

My poll questions were mostly centered around preferences and the self. The questions on preferences were the most straightforward to answer: examples included red or white wine, french fries or tater tots, cooking or cleaning. I scattered the preference-based questions throughout this project in order to balance out the harder ones, to lighten up the mood, and also because I noticed early on that easy, impersonal questions tended to get more votes. Towards the tail end of the project, numerous people told me that they had gotten into a routine of looking forward to voting on my polls for the day. I believe the easier questions helped ease some people into this. Most of the preference-based questions were about food, which is not surprising to me because I think about food a lot. (A few months ago, I traveled with a friend, and she pointed out during our trip that I like to ask about what we’re eating for lunch at 9:00am.)

The other, deeper questions didn’t follow a set theme, but they required some introspection and looking back on specific moments in one’s life. I retroactively classified all the poll questions by how difficult I thought they were to answer into Easy, Medium, and Hard. The Easy category mostly consisted of preference-based questions. The Medium and Hard categories consisted of questions that were personal and called for some deeper thought. My distinguishing factors between those two categories were that, for Hard questions, both answers contained an implicit admission of one’s flaws and weaknesses (or the perception of one’s flaws and weaknesses) and there was no “better” answer among the two. Personal questions that did not fulfill these criteria were classified as Medium. Obviously, in the end, these designations are still subjective: I deemed 30 of the poll questions as Easy, 45 as Medium, and 25 as Hard. (That these numbers turned out so nicely is a coincidence; I didn’t realize this until after I had finished sorting all the questions.)

It can be challenging to talk about feelings or vulnerabilities on Instagram, a social media platform that is largely based around glossy, polished visual images — perhaps, it can be even more challenging to ask people about their feelings or vulnerabilities. However, I noticed a sharp upward trend in engagement almost immediately, so I kept going, sometimes posting multiple polls a day. Before March 2020, I would typically get about 30 or 40 votes on my Instagram polls. Among my 100 poll questions, 38 of them received 100 or more votes, the vast majority of which (34) fell in the second half of the project. I would eventually go on to have a streak of 12 consecutive polls that got over 100 votes each, and this streak was broken by a question that got “only” 98. For a regular, not-famous person on Instagram with a measly 700 followers, these figures were astronomical — especially so when you also consider that the number of people who view my Instagram Stories tends to range between 180 and 230. In other words, for some of my polls, I had gotten over half of my total viewers to vote. I don’t know the Instagram algorithm that determines whose Stories are displayed first on one’s feed, but I imagine that my high engagement rate further boosted my Stories, ensuring that people were more likely to see that I had just posted another new poll.

(An interesting side observation: while the number of people who voted on my polls increased quite a lot over this time, the number of people who viewed my Stories did not. My aforementioned 180-230 range has remained fairly constant for the past year or so. My Instagram Stories tend to be viewed by the same 180-230 people, meaning that the remainder of my 700 followers are probably not very active on Instagram, don’t really interact with my stuff, or have muted my Stories. This means that the growth of popularity in my poll series was primarily drawn from my existing audience, as opposed to the development of a new audience.)

More than the number of votes I was getting, though, the thing I loved about my polls was that it led to many conversations. Without any prompting on my end, I began receiving messages from people who wanted to further clarify or explain why they chose the answer that they did. Some of these reflections spanned several paragraphs. I began thinking of my Instagram polls as a bite-sized, digital, secular confessional booth of sorts. It was really nice getting to learn more about people’s thoughts and I liked that even people I was not very close to felt comfortable opening up to me. These polls helped me reconnect with people I had not spoken to in a long time. My polls were also being used for offline conversations; I saved all my polls in a Highlight on my profile, and numerous people told me that they went through the entire log of polls with their roommates, friends, and partners — strangers who did not know me. People were discussing their own answers to my questions and also reflecting on the way the rest of my friends had voted. It seemed like my polls were inspiring people to do some self-reflection, so I guess that’s my contribution to society for the year. People also volunteered ideas for future questions, and I ended up posting three of them.

I did not anticipate the high engagement of my polls, nor did I expect that they would garner any additional attention beyond the several seconds it takes a person to vote. I think that this project’s success is partly due to my ability to ask good, direct questions (if I may say so myself) as well as the possibility that my polls served as a break from all the other things that people were seeing on Instagram and on the news. However, a lot of credit goes to the nature of the Instagram poll function itself. I can think of at least three reasons why Instagram polls are alluring:

It’s fun to participate in something instead of just passively consuming content, especially when the barriers to participation are so low.

It’s fun to see how other people have voted.

The perceived popularity of something has the potential to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. When something is regarded as popular, people are more likely to pay attention to it and more likely to think highly about it. As much as we like to think of ourselves as having refined, independently-formed tastes, many of us get our cues on what to like based on others; it is a part of being able to process an overwhelming amount of information and to form opinions. The reverse holds true, too. You see this phenomenon unfold in mainstream pop music, restaurant reviews, and viral social media posts. The beauty of Instagram polls is that the voter does NOT know how many people have voted or have viewed it. (I mean, you could make educated guesses based on the vote breakdown and how much time has passed since the poll was posted. But that is, at best, a guess, and by then you have already voted, so.) This quality reduces the likelihood that someone abstains from voting simply because they think it’s an unpopular poll and because they don’t want to be the first person to vote. I do know of people who avoid being the first to “like” a social media post.

Almost immediately, within the first 10 questions or so, some people asked me if I was tracking the poll results or if all these questions were for a larger purpose. They know me well, I guess. Originally, the answer was truly no. My intention was to take it question by question and just enjoy the conversations that these questions were inspiring.

And then, the bots showed up.

Observations on the voting patterns of instagram bots

For the uninitiated: well, where do I start? My understanding of Instagram bots is that they are dodgy spam accounts that don’t look like they are run by real people. These bot accounts sometimes engage with real people’s accounts by liking posts, commenting on posts, or viewing Stories. Their comments are pretty questionable: “Get 1000 followers by checking out the link in my bio!” is a popular one. Some bot accounts are deployed to boost follower counts, views, and likes. If you ask me, they’re like the Instagram, modern-day edition of the Nigerian prince scam email; bot accounts are pretty easy to spot right away, everyone I know instinctively ignores them, and you never hear about any good coming from them. I honestly don’t really understand why bot accounts are so bad at not coming across as bot accounts. But then again, what do I know?

My Instagram account is public, meaning that anybody who looks up my profile can view my Stories. I’m just a random potato, so I had never really given much thought to bot accounts showing up on my profile. In the eight years that my Instagram account has been in existence so far, I’ve probably received (and deleted) fewer than ten comments from bot accounts. But I guess the rising relative popularity of my polls put me on a radar for bots, or something. I got my first bot vote on my sixth poll (sour cream and onion, or salt and vinegar chips?) and from that point on, there was a small but steady stream of bots present and voting. At the peak of this, my 19th poll (“ok”, or “okay”?) received votes from nine bot accounts, which accounted for one-ninth of the total votes. Prior to these Instagram polls, I had seen bot accounts among my Stories viewer list before, but it was an uncommon occurrence. Like I said, I’m just a random potato.

Because I had nothing else to do, I began paying attention to the way these bot accounts were voting. I compiled the data from the 30 or so polls I had posted during this period thus far on a spreadsheet. When all the information came together on one screen, I noticed some distinct patterns. As it turned out, these bot accounts were voting on my polls in very predictable ways:

When there were multiple bot accounts voting on the same question, they ALWAYS voted for the same answer. Regardless of whether there were three, six, or nine of them — complete, absolute, perfect uniformity. (Side note: from my observations, bot accounts are not predisposed to voting only for the answer on the left, or only the right, of the poll.)

The bot accounts ALWAYS voted for whichever answer was leading at the time. Upon creating the spreadsheet and filling in the results of all the polls posted so far, I saw that the bot accounts had a perfect, and I mean 100% perfect, track record of voting for the answer that ultimately won. This led me to keep an eye on bot account votes during subsequent polls as they were ongoing. Bot accounts never cast the first votes of any of my polls; they tended to only come in during the tail end of the 24-hour period. If a particular poll was very close in a particular moment (in the 45% to 55% per answer range), a bot account would simply view the poll and not vote. This voting pattern helps explain why, when I first created the spreadsheet, the bot accounts had always been successful in voting for the answer that ultimately won.

Eventually, the bots fucked up on two occasions. On my 37th poll (would your close friends describe you as easygoing?), No maintained a lead margin of greater than 10% for more than half a day. Three bot accounts came in and also all cast their votes for No. However, in one of the most exhilarating last-minute twists in this whole project, I received a lot of votes from allegedly easygoing friends for Yes in the final few hours, enough to change the outcome. This was the first time the bot accounts picked “the wrong side”, so to speak. The only other time this happened in my project was on my 47th poll (would you rather give up cheese or spicy food for life?), in which the sole bot account vote was for the answer that was in the lead at that moment, but that answer ultimately lost, 49% to 51%.

Additionally, in my spreadsheet, I calculated the “real” results of individual polls after removing the votes from bot accounts. There was no instance in which the presence of bot account votes entirely swung the results another way. The closest I got to that outcome was on the 15th poll (is it scarier to be always alone, or around people 24/7?), in which removing all bot account votes led to a tie. This point is to clarify that the bots always voted for whichever answer was leading, but they never made an answer win.

I am not an expert on bot accounts. I can only report what I see. I am open to the possibility that my observations on the voting patterns of bot accounts on my polls do not reflect the way all bot accounts vote. But both observations (bot observations? hahaha I’m so funny) were fascinating to me! If bot accounts are able to always vote in sync and are able to always vote for whichever answer is in the lead, I wonder if bots have the technical capabilities to read a user’s ongoing Instagram poll results in order to be able to vote in the way they did on mine. I wanted to contact some of the bot accounts who had voted on my polls and interview them for this essay, but I decided it was probably best that I didn’t.

Bots are bots — and yet, for whatever reason, I kept ascribing personalities to these faceless, collective bots that were voting. Did they prefer potato salad or chicken salad? Had they already met someone they would seriously want as a life partner? Did they wish that they had worked harder five years ago? When three bot accounts voted to say that they considered themselves less cheerful than the average person, I briefly, genuinely, felt sorry for them. Maybe they all had rough childhoods. It’s not easy to be a bot these days, especially in this economy.

After lurking around for 42 polls, the bots left, never to be seen again for the remaining 53 questions of the project. No more votes, no more views, not another peep from them. One possible explanation for this could be that all the bot accounts that voted on my polls had been deployed by just one entity — and that, for whatever reason, I had eventually ceased to be a subject of interest for this entity and their bots. I guess I just didn’t want to GET 1000 FOLLOWERS. If this explanation were true, it would further explain why these bots had managed to all vote in unison, but it does not solve the mystery of how they were able to always vote for whichever answer was in the lead. (For what it’s worth, there was no real indication to me that all that bot accounts that had voted on my polls had been deployed by just one entity. This is just my best speculation.)

Of course, I didn’t know during my 47th poll that it was the last time the bots would show up and vote. I hawkishly monitored my polls over the following week for signs of bot activity; no dice. By then, I was 70 polls in and I was like...alright, alright, let’s do 100. And so, here we are.

Other key insights from 100 instagram polls

For greater accuracy, all votes from bot accounts were not counted for the official calculation of results. Additionally, where applicable, all percentages have been rounded to one decimal place.

Ensuring fairness and minimizing biases

It is very challenging to write a question that is universally understood and also fair. Despite my best efforts, I received numerous messages throughout the project that made me realize the sender had misunderstood the intent of my poll question. For example, my 77th poll question was “Your favorite bougie indulgence” and voters could choose between oysters and truffles.

“Is this even a question?” someone I went to college with wrote. “You can get good oysters for $1 each, but truffles are exorbitantly expensive.”

After some back-and-forth, I clarified that I was actually trying to ask which one people liked the taste of better.

“Even if they cost the same”, I replied, “you’d get truffles?”

“Probably not”, he wrote. But by then, it was TOO LATE and his vote for truffles had already been recorded.

I found out that questions containing negatives were also unideal. My second poll question asked which one people would rather give up forever, ice cream or fried chicken. I got a message from a friend saying that she had misread the question and picked fried chicken, since it was her favorite of the two. By chance, someone else who messaged me several hours after that had mistakenly picked ice cream for the exact same reason, so their incorrectly cast votes cancelled each other out. I learned from these mistakes (and others) and tried to keep the wording in my questions as straightforward as possible. However, it is very possible that there were additional instances of confusion that I still don’t know about because nobody messaged me about them.

Basic statistics courses address various forms of response biases in surveys, including:

Disproportionately drawing certain types of respondents — for instance, many optional customer feedback surveys tend to attract responses from customers who are either extremely satisfied or dissatisfied, because there’s little incentive for those in the middle to share their opinions.

If respondents have to answer several questions consecutively, it’s human nature to assume connections between them even if every question was intended to be completely independent of each other. I recall a textbook example of this in which people were asked (A) to rate their own happiness on a scale of one to ten and (B) if they were dating anyone. When these two questions were presented in reverse order (question B, and then question A), those who said they were single reported noticeably lower happiness scores than other single people who received (and answered) the question on happiness first. The sequence and number of questions can have an effect on the final results.

In order to avoid either of these types of biases, I tried to stick to poll questions with no ascribed moral or social judgment for either answer. The more personal questions (the ones classified as Hard) were set up so that both answers were equally revealing. Additionally, on the days that I posted multiple polls I tried to ask questions that were completely topically unrelated to each other and I spaced out the hard-hitting questions across the project.

2. The most popular not-easy poll questions

These were the 5 Medium or Hard poll questions that received the highest number of total votes. As mentioned earlier, bot votes were not counted in my calculations. (If you want to see the complete list of questions sorted in descending order of votes received, including all the Easy ones, you can find them on my spreadsheet.)

Poll #98: Which do you think you’re more likely to do in the next 10 years?

Options: “become a parent” or “move overseas”

Total number of votes: 119

Result: 47 votes for become a parent, 72 votes for move overseas (39.5% to 60.5%)

Poll #62: You are more annoyed by people who are

Options: “very pretentious” or “not curious”

Total number of votes: 117

Result: 88 votes for very pretentious, 29 votes for not curious (75.2% to 24.8%)

Poll #99: Deep down, do you think the world will be better or worse off in 20 years than it is today?

Options: “better” or “worse”

Total number of votes: 115

Result: 57 votes for better, 58 votes for worse (49.6% to 50.4%)

Poll #75: You are more annoyed by a friend who

Options: “flakes” or “never initiates”

Total number of votes: 114

Result: 84 votes for flakes, 30 votes for never initiates (73.7% to 26.3%)

Poll #83: You feel more guilty about the way you spend your

Options: “money” or “time”

Total number of votes: 113

Result: 36 votes for money, 77 votes for time (31.9% to 68.1%)

3. The closest and least close polls

For each poll question, I calculated the absolute difference in the percentage of votes received for each of the two answers.

These were the three closest polls:

Poll #15: It is scarier to be

Options: “always alone” or “around people 24/7”

Total number of votes: 70

Result: 35 votes for always alone, 35 votes for around people 24/7 (50% to 50%)

Poll #99: Deep down, do you think the world will be better or worse off in 20 years than it is today? (Poll #99 also appeared in Insight #2)

Options: “better” or “worse”

Total number of votes: 115

Result: 57 votes for better, 58 votes for worse (49.6% to 50.4%)

Poll #50: Which type of pasta do you prefer?

Options: “strands” or “pieces” (I gave examples of both within the frame. “Strands” include spaghetti, angel hair, and fettuccine. “Pieces” include penne, farfalle, orecchiette, and rotini. There might be more legit, technical words to describe these categories of pasta, but this is the best I had.)

Total number of votes: 99

Result: 49 votes for strands, 50 votes for pieces (49.5% to 50.5%)

These were the three least close polls:

Poll #4: Without looking, do you know how many likes your most-liked Instagram post got?

Options: “yes” or “no”

Total number of votes: 89

Result: 9 votes for yes, 80 votes for no (10.1% to 89.9%)

Poll #88: Favorite day of the weekend

Options: “Saturday” or “Sunday”

Total number of votes: 107

Result: 96 votes for Saturday, 11 votes for Sunday (89.7% to 10.3%)

Poll #82: Which one have you felt more of in your life: you being jealous of others, or you believing that others are jealous of you?

Options: “you of others” or “others of you”

Total number of votes: 98

Result: 87 votes for you of others, 11 votes for others of you (88.8% to 11.2%)

The mean absolute difference in the percentage of votes received for the two answers in a question was 29.7% across 100 questions. A 30% difference in a vote breakdown means that 35% of respondents voted for one answer and 65% voted for the other (or vice versa). The median absolute difference for the same set of data was 24.4%. In other words, the “least remarkable” poll in terms of vote breakdown, so to speak, had roughly a 38% to 62% split (or vice versa).

For further exploration, I also calculated the mean and median absolute differences in the percentage of votes received for each of the two answers among the questions in each category.

4. How often I agreed with the majority of my voters

Whenever I posted a new poll, I also noted down what my answer would have been for that question. As of writing, Instagram does not let users vote on their own polls.

I was able to compare my own choices, side by side, with “winning answers” to 97 poll questions. The three exceptions to this were:

Poll #15, which ended in a dead tie and so there was no “winner”

Poll #19, because I actually use both “ok” and “okay” in texts — clear sign of a sociopath

Poll #74, which was a question submitted from a friend’s brother and was about people’s greater motivation in participating in my poll series (a very meta question, which I enjoyed) — I could not have an answer of my own, since I wasn’t really a participant, per se

Out of 97 questions, my answer matched with the “winner” 39 times, which means that I agreed with the majority of my voters on 40.2% of the poll questions. In other words, my answer disagreed with the majority of my voters on 59.8% of the questions.

When breaking this down by categories, you can see that I agreed with the majority of my voters more often on Medium and Hard questions.

Also, unlike 90% of my voters, I DO know off the top of my head how many likes my most-liked Instagram post got. I’ll own up to that.

5. What I learned about myself from these questions

I posted polls as ideas came to mind, meaning that the questions I asked were typically reflections of things I had recently thought about or experienced. For instance, I posted a poll question asking about people’s preferences between sweet and salty popcorn because I was literally eating popcorn at that moment. My own polls, especially the Medium and Hard questions, made me more conscious of the topics I find interesting and enjoy talking about with friends: relationships, past struggles or mistakes, self-perception, insecurities, and personal motivations. I mean, I already kind of knew this, but the project solidified this awareness for me. I really enjoy people’s presentation of their own narratives in the context of their life stories — listening to how they evaluate their pasts and how it makes them who they think they are today.

In both my personal and professional lives, I really like straightforward, concise answers. My approach in answering challenging questions tends to involve taking a bit of time alone to consider all the information at hand, and then forming a definite answer of my own. If there is no new information available, my answer rarely waffles after I’ve made up my mind. I might share my answer with other people, but I rarely turn to them to collaborate on arriving at the answer. For better or for worse, I am quick to distill a question into a binary and then pick my answer. I almost never find a binary question to be so nuanced that I truly have no opinion. (Real-life examples of high-stakes binary questions: Should I accept this job offer or not? Should I move to this new city or not? Should I date this person or not? Should I sign a lease for this studio apartment, or for the one-bedroom located five blocks away?) As it turns out, this personality trait is helpful in making Instagram polls. I got a number of messages from my friends to my polls along the lines of “I didn’t vote because I couldn’t decide!” I was genuinely baffled by this. How could you not know? I wondered. So, my Instagram polls made me more aware of the way I think, and it was also a reminder for me that our brains do not all work in the same ways.

Conclusion

My 100 Instagram polls spanned 48 days and I really enjoyed them. However, you have to know how to quit when you’re ahead. I didn’t want to make a commitment to being “that friend who posts polls on Instagram” indefinitely. Some people were enjoying my questions, engagement was high, and the bots didn’t seem to be coming back — so it was time to exit gracefully. I don’t like to make other people feel like they’re wasting their time; I believe that, had I kept going, I would soon run out of good questions to ask.

Importantly, I had a lot of fun because I myself would have loved to see and answer these questions. I might start bringing printouts of my 25 favorite questions to parties in the future...whenever it is we have parties again, that is. In the meantime, I will be reorganizing my list of friends based on the answers they chose in my polls.

Additional materials

The spreadsheet I used for this project, which includes:

All 100 poll questions and answers, sorted by category

All 100 sets of vote breakdowns, including records of how bot accounts voted

All 100 sets of results, sorted by vote count

All 100 sets of results, sorted by absolute difference